A Day With: Agoraphobia

[Editor’s Note: This piece is part of an ongoing series of personal essays on what it’s like to live with a mental health diagnosis. Each piece describes a singular and unique experience. These essays are not meant to be representative of every diagnosis, but to give us a peek into one person's mind so we may be more empathetic to all.]

A tall, thin man in a suit was seated in our living room. He stood as I entered.

“You see,” Benton continued, “as you avoid all the places where you have panic attacks, you eventually only feel ‘safe’ at home because the attacks don’t happen here. Your dad told me it has been six months since you left this house.” Tears began to form in my eyes. He knew about my secret and I was terrified he would insist I go outside. I couldn’t. I wouldn’t. “I’m sorry, but I only have bad migraine headaches and that is why I don’t leave my house,” I lied. “Yes, I know you have migraines, but they are secondary to your panic and Agoraphobia. I am not going to ask you to step outside just yet. I would like to visit and talk with you twice a week here. There is an end in sight, Katie. You are intelligent, yet full of fear. We can overcome this.” And so my journey began. I agreed to meet with Benton twice a week. My first question to him was, “Why is this happening?” “We have to get to the root of your panic, your fear of fear. Each person with this condition may have underlying reasons that precipitate this disorder. If you will trust me and be forthright about your life, I am confident that you can get to the other side of this.” So we talked. We talked about my parents, my school experiences, my peers, and my dreams. None of these seemed to trigger much reaction inside of me. We seemed to be reaching a dead end. Benton slowly encouraged me to take shorts trips outside of my safe home. This method of healing is called “desensitization.” Each time one succeeds at facing their fears by traveling through them, they lessen. Would you believe that my first outing was to walk to the mailbox—a mere 15 feet from the front door? I was anxious but did not panic.

“You see,” Benton continued, “as you avoid all the places where you have panic attacks, you eventually only feel ‘safe’ at home because the attacks don’t happen here. Your dad told me it has been six months since you left this house.” Tears began to form in my eyes. He knew about my secret and I was terrified he would insist I go outside. I couldn’t. I wouldn’t. “I’m sorry, but I only have bad migraine headaches and that is why I don’t leave my house,” I lied. “Yes, I know you have migraines, but they are secondary to your panic and Agoraphobia. I am not going to ask you to step outside just yet. I would like to visit and talk with you twice a week here. There is an end in sight, Katie. You are intelligent, yet full of fear. We can overcome this.” And so my journey began. I agreed to meet with Benton twice a week. My first question to him was, “Why is this happening?” “We have to get to the root of your panic, your fear of fear. Each person with this condition may have underlying reasons that precipitate this disorder. If you will trust me and be forthright about your life, I am confident that you can get to the other side of this.” So we talked. We talked about my parents, my school experiences, my peers, and my dreams. None of these seemed to trigger much reaction inside of me. We seemed to be reaching a dead end. Benton slowly encouraged me to take shorts trips outside of my safe home. This method of healing is called “desensitization.” Each time one succeeds at facing their fears by traveling through them, they lessen. Would you believe that my first outing was to walk to the mailbox—a mere 15 feet from the front door? I was anxious but did not panic.

“My name is Dr. Benton,” he said as he reached to shake my hand. “I’ve been meeting with your parents as they are concerned about you. I’m a psychologist who specializes in Agoraphobia, the fear of leaving your home.” My freshman year at the local university was a disaster. I couldn’t concentrate on my studies and I experienced awful episodes when I felt like I was dying. Imagine you have a booted foot stuck in a railroad tie. As a train approaches, you cannot free yourself. Your heart begins to race; you feel dizzy and faint. Sweat streams down your face and your hands tremble. You may wet yourself and vomit at the same time. Imagine now that this horridness occurs randomly—while at the movies, driving a car, or shopping at the mall. Welcome to the world of panic.

“Katie, you will find that if you do panic that your body can only keep up that adrenaline rush for about 45 minutes. There is always an end to an attack. The more you become comfortable with these small steps, the less likely you are to panic. Today I would like you to walk three times around your yard.” “Dr. Benton, I was thinking about a time when I went to live with my grandmother for about a year. My mom had heart problems and my dad, of course, worked. I think I was about five-years-old at the time. I know it isn’t nice to say this, but she terrified me. She was really old, mean, and set in her ways. As a young child in her care, she bullied and threatened me. I had to bathe twice a day and I also remember her insisting that I eat everything she served even if it gagged me. I cried all the time and she would smack my face to get me to stop.” “Katie, that is truly a traumatic experience for a young child. I’m thinking that the fear that you experienced there may have been buried in your mind and is coming out now.” We began to walk and talk during my sessions. We discussed basic child development—how young children cannot process trauma without guidance. We talked about leaving for college as a trigger. The only time I had left my parents for an extended period of time was my time with my grandmother. And, of course, I was too young to verbalize my feelings to anyone. My grandmother’s message was, “You’re a bad kid,” and I bought it. Leaving for college seemed to duplicate that scary episode. The day came when Benton wanted me to walk down my street, alone. He prepared me by soothing my anxiety and stating that I was ready for the challenge. Off I went, humming a favorite song as he had suggested. I began to feel anxious but played our conversations over and over in my mind. I did it! I walked for a half hour! Glad to get home again, I was nonetheless excited about my progress. A year passed. Taking small steps, I broadened my boundaries. Eventually, I took short trips to the bank, the post office and the like. I drove again and attended therapy sessions at Benton’s office. Having an emotional disorder was certainly no fun. I will say, however, that I am better off for it. I’m tolerant and patient with others who struggle. I’ve found that when I share my story many people share a story of their own. A was once for Agoraphobia. A is now for Achievement.

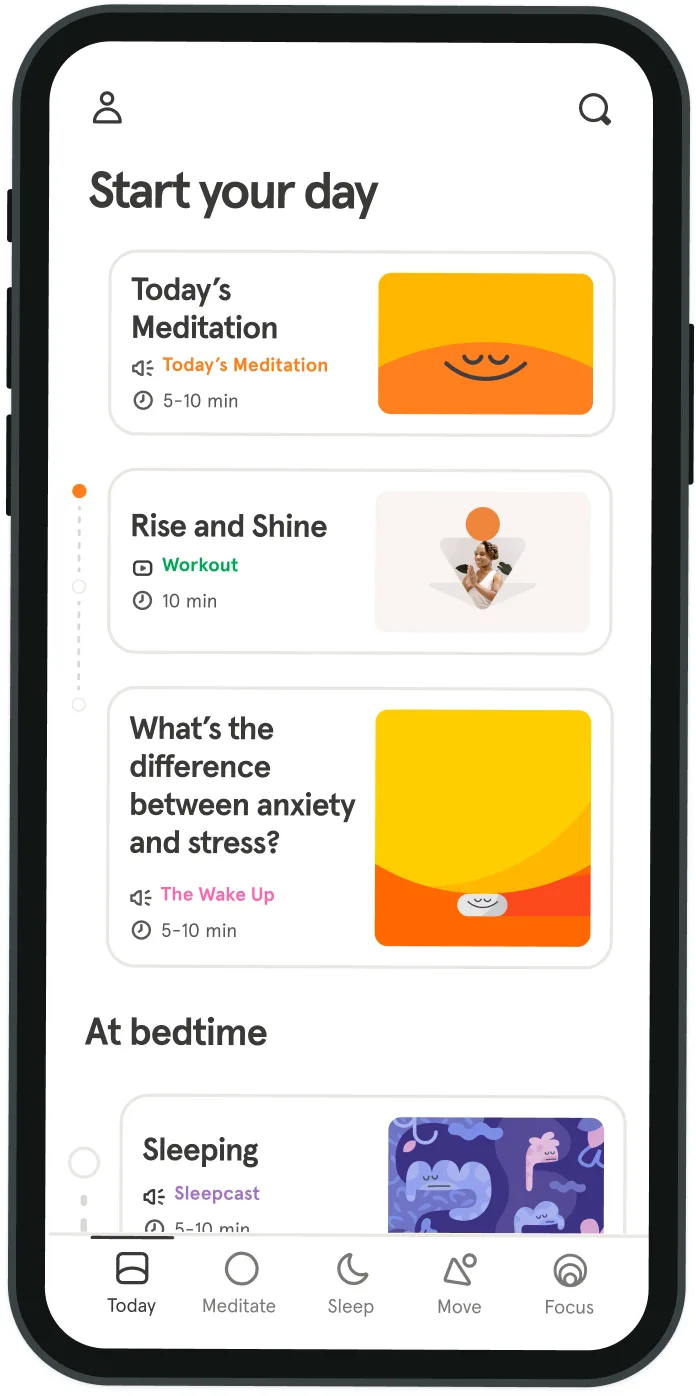

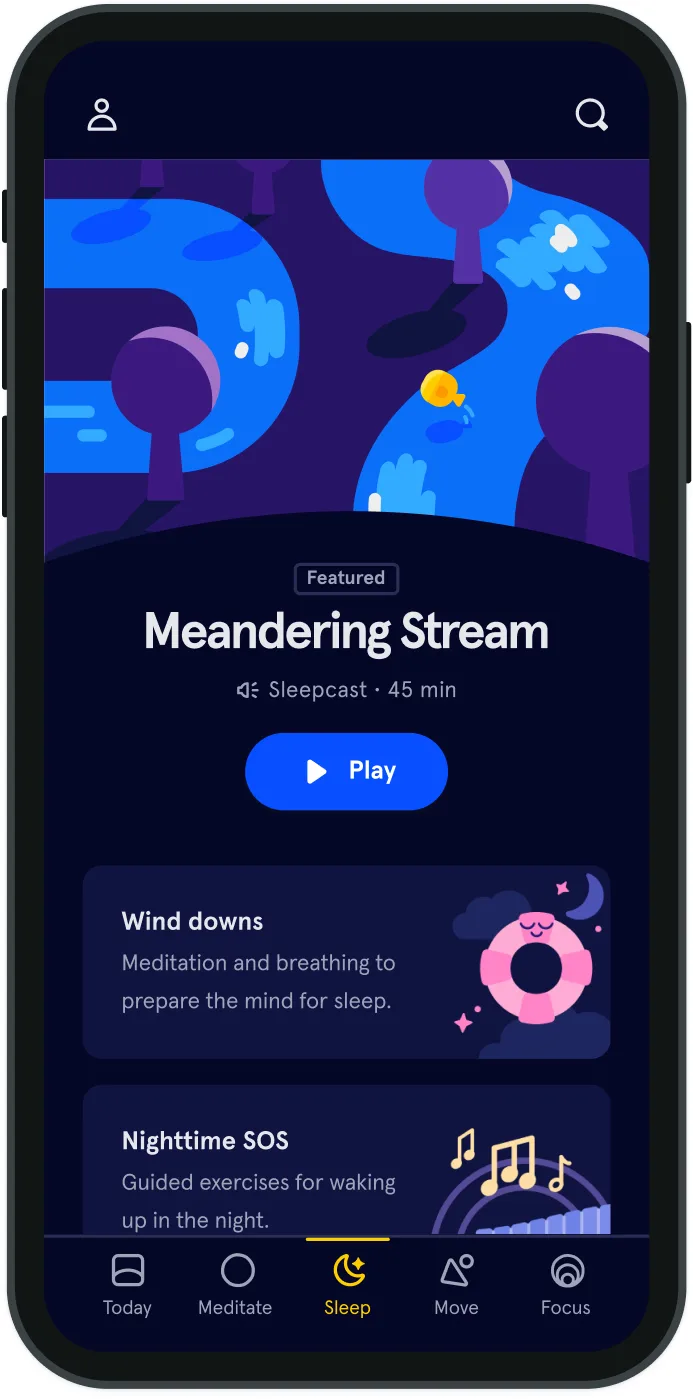

Be kind to your mind

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

- © 2024 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice