A Day With: OCD

[Editor’s Note: This piece is part of an ongoing series of personal essays on what it’s like to live with a mental health diagnosis. Each piece describes a singular and unique experience. These essays are not meant to be representative of every diagnosis, but to give us a peek into one person's mind so we may be more empathetic to all. Trigger warning for OCD, anxiety, and violent imagery. Those struggling with these disorders, or those who find themselves suggestible or find it difficult to deal with upsetting thoughts, might choose to avoid reading the piece.]

It was a warm summer night, and all the kids in the neighborhood were playing kick-the-can while the parents spoke over the fences in their yards. The shots rang out—I could see the back of the lone gunman as he walked down the alley toward our house—aiming at anyone within his eyesight.

Because that’s the thing about my OCD: my brain goes from zero to sixty, from neutral to destructive, in any situation it can. When I get through the morning ritual, there’s no relief in having kept anything at bay. Because I have a closet. Yes, I also have work. But I have a closet, and it is never correct. To my friends, it’s flawlessly organized by season, style, and color with everything easily visible. To me, it’s a jungle-mess full of ugly things that don’t fit and will make me a social outcast—this needs daily taming. So, I log into my computer, deal with email, check the socials, and try to do some writing until the thoughts of my disorganized T-shirt section have overpowered everything else. So like yesterday, I go into the closet and ask the same questions that I have every day for the past nine months: does it fit? Is it cool? Will it repel people? Why did I even buy this? Whether I just re-categorize or pull items for donation, it can take two or three hours during which I do some work but always with a rushed sense of incomplete business in the closet. For some reason, my appropriate focus is pretty solid in the afternoon. I can be productive and mostly not distracted between 1-5 p.m. Unless I have to leave the house. Then, outdoor obsessive-compulsive disorder (OOCD) kicks in. Where there is less control, there is more grasping for it. Today I had to go to the bank. The car gives me my greatest sense of freedom but I also fantasize constantly about accidentally running someone over with my car. Even with hypervigilance, I catastrophize anything I can. In line at the bank, I wonder which of these people are the robbers that will hold us all hostage. I look for exits, run through first-aid procedures to help whoever gets shot, wonder who in my family will realize (or care) I’m in danger. On the way home, I’m rerouted and drive through a pass with some elevation which means I’m sure the car will flip over the guardrail and crash into the ravine. I see the plunge in my mind’s eye. Of course, I get home safe from hostage situations and fatal car crashes. My closet is acceptable. I have nothing to fix, clean, or straighten as I did all that yesterday to satisfy an overwhelming compulsion. So I’m free to finish maybe another hour of work. Then I have to walk the neighbor’s dog. This beautiful, sweet puppy, I’m sure, will die in my presence. If it’s not hit by a car or attacked by a coyote, the specific kibbles I dish out from the already-open bag of food will be poisoned. For the next hour after walking and feeding, I check in on the pooch every twenty minutes. (The dog is fine.) Every evening, around 6 p.m., I do a “final check” on my externals to make sure things are in place and the apartment is clean before I can feel relaxed enough to either watch Netflix or brave the OOCD and try to be social. Life depends on these behaviors: if that candle on my coffee table is aligned properly with the stack of magazines, on which the remote must rest diagonally. Before my diagnosis, I didn’t understand that such habits are nonsensical. The implications of my obsessions and compulsions felt critical. So many nights, I’d forego a party in order to clean up after my roommates. I’d skip class to arrange canned food alphabetically in the cabinet. I’d lie about all of it. What I couldn’t see was the real impact of my disease: the failing grades, the lost social connections, missing news and events, poor health. While my eating and sleeping habits are pretty solid nowadays, it’s still difficult to be social. I have a job that frequently requires evenings out, but as a textbook introvert, that means pushing myself and faking confidence. Tonight, I have to go to a play held in a small room, which offers little comfort. I don't know anyone else there. I’ve met the actor once. After the performance, I bolted for the door. Halfway down the block, I had to check myself about why I didn’t stay to acknowledge the actor: my hair is terrible. My breath is gross. Everyone else is more interesting. The second I open my mouth he’ll tell his manager I suck, I’ll lose business, then more business, then I’ll be homeless. (Ugh!) So I went back in and had a most lovely chat. When I was diagnosed in college decades ago, I didn’t have the option to try medication. The only treatment recommended and available was cognitive behavioral therapy. It remains one of the standard treatments for the illness but required years of difficult, ugly work, and hourly maintenance. The symptoms can sneak in so quietly. In the throes of an episode, logic is meaningless and focus is impossible. Control is a key issue for people who experience OCD; gaining a greater understanding of what that means helped me. Journaling, especially after a particularly horrible night of dreams, has been a valuable way to more objectively consider the significance of thoughts and actions. Replacing ritualistic behavior with meditation can change an entire day. Within five minutes of meditating, the urge to reevaluate my entire apartment is gone. Taking conscious control of the feelings around my lack of control, oddly, has been incredibly empowering. During the day, I recognize choices and try to make the most healthy ones. On the days I self-care well, my nights are restful. At least I don’t remember the monsters!

My neighbors were dropping to the ground, bloody. I needed to get to the front door of my house and secure my mom and sister inside. I ran as fast I could through gangways until I reached our house and ran inside. Then I woke up. Graphic and terrifying dreams are part of living with Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Since I was a child, dreams of deadly plane crashes, murderous monsters, and of course, gunmen, haunted my nights. In every scenario, I am either a victim or a powerless observer. There’s never a resolution. I just wake up and start the day. Daytime is different but no better. Obsessive thoughts about order and cleanliness distract me. I’ve recently starting using my iPhone’s Reminders feature to keep me focused on legitimately healthy behaviors. I wake at 7 a.m. with reminders to meditate, do a series of stretches, and take some morning vitamins and a juice. While this sounds normal and healthy, for me it describes “positive control.” The motivation isn’t so much about being healthy as it is avoiding the extreme results of not doing these things which are, of course, spontaneous cancer, immediate obesity, and quick-fire insanity.

Because that’s the thing about my OCD: my brain goes from zero to sixty, from neutral to destructive, in any situation it can. When I get through the morning ritual, there’s no relief in having kept anything at bay. Because I have a closet. Yes, I also have work. But I have a closet, and it is never correct. To my friends, it’s flawlessly organized by season, style, and color with everything easily visible. To me, it’s a jungle-mess full of ugly things that don’t fit and will make me a social outcast—this needs daily taming. So, I log into my computer, deal with email, check the socials, and try to do some writing until the thoughts of my disorganized T-shirt section have overpowered everything else. So like yesterday, I go into the closet and ask the same questions that I have every day for the past nine months: does it fit? Is it cool? Will it repel people? Why did I even buy this? Whether I just re-categorize or pull items for donation, it can take two or three hours during which I do some work but always with a rushed sense of incomplete business in the closet. For some reason, my appropriate focus is pretty solid in the afternoon. I can be productive and mostly not distracted between 1-5 p.m. Unless I have to leave the house. Then, outdoor obsessive-compulsive disorder (OOCD) kicks in. Where there is less control, there is more grasping for it. Today I had to go to the bank. The car gives me my greatest sense of freedom but I also fantasize constantly about accidentally running someone over with my car. Even with hypervigilance, I catastrophize anything I can. In line at the bank, I wonder which of these people are the robbers that will hold us all hostage. I look for exits, run through first-aid procedures to help whoever gets shot, wonder who in my family will realize (or care) I’m in danger. On the way home, I’m rerouted and drive through a pass with some elevation which means I’m sure the car will flip over the guardrail and crash into the ravine. I see the plunge in my mind’s eye. Of course, I get home safe from hostage situations and fatal car crashes. My closet is acceptable. I have nothing to fix, clean, or straighten as I did all that yesterday to satisfy an overwhelming compulsion. So I’m free to finish maybe another hour of work. Then I have to walk the neighbor’s dog. This beautiful, sweet puppy, I’m sure, will die in my presence. If it’s not hit by a car or attacked by a coyote, the specific kibbles I dish out from the already-open bag of food will be poisoned. For the next hour after walking and feeding, I check in on the pooch every twenty minutes. (The dog is fine.)

Every evening, around 6 p.m., I do a “final check” on my externals to make sure things are in place and the apartment is clean before I can feel relaxed enough to either watch Netflix or brave the OOCD and try to be social. Life depends on these behaviors: if that candle on my coffee table is aligned properly with the stack of magazines, on which the remote must rest diagonally. Before my diagnosis, I didn’t understand that such habits are nonsensical. The implications of my obsessions and compulsions felt critical. So many nights, I’d forego a party in order to clean up after my roommates. I’d skip class to arrange canned food alphabetically in the cabinet. I’d lie about all of it. What I couldn’t see was the real impact of my disease: the failing grades, the lost social connections, missing news and events, poor health. While my eating and sleeping habits are pretty solid nowadays, it’s still difficult to be social. I have a job that frequently requires evenings out, but as a textbook introvert, that means pushing myself and faking confidence. Tonight, I have to go to a play held in a small room, which offers little comfort. I don't know anyone else there. I’ve met the actor once. After the performance, I bolted for the door. Halfway down the block, I had to check myself about why I didn’t stay to acknowledge the actor: my hair is terrible. My breath is gross. Everyone else is more interesting. The second I open my mouth he’ll tell his manager I suck, I’ll lose business, then more business, then I’ll be homeless. (Ugh!) So I went back in and had a most lovely chat. When I was diagnosed in college decades ago, I didn’t have the option to try medication. The only treatment recommended and available was cognitive behavioral therapy. It remains one of the standard treatments for the illness but required years of difficult, ugly work, and hourly maintenance. The symptoms can sneak in so quietly. In the throes of an episode, logic is meaningless and focus is impossible. Control is a key issue for people who experience OCD; gaining a greater understanding of what that means helped me. Journaling, especially after a particularly horrible night of dreams, has been a valuable way to more objectively consider the significance of thoughts and actions. Replacing ritualistic behavior with meditation can change an entire day. Within five minutes of meditating, the urge to reevaluate my entire apartment is gone. Taking conscious control of the feelings around my lack of control, oddly, has been incredibly empowering. During the day, I recognize choices and try to make the most healthy ones. On the days I self-care well, my nights are restful. At least I don’t remember the monsters!

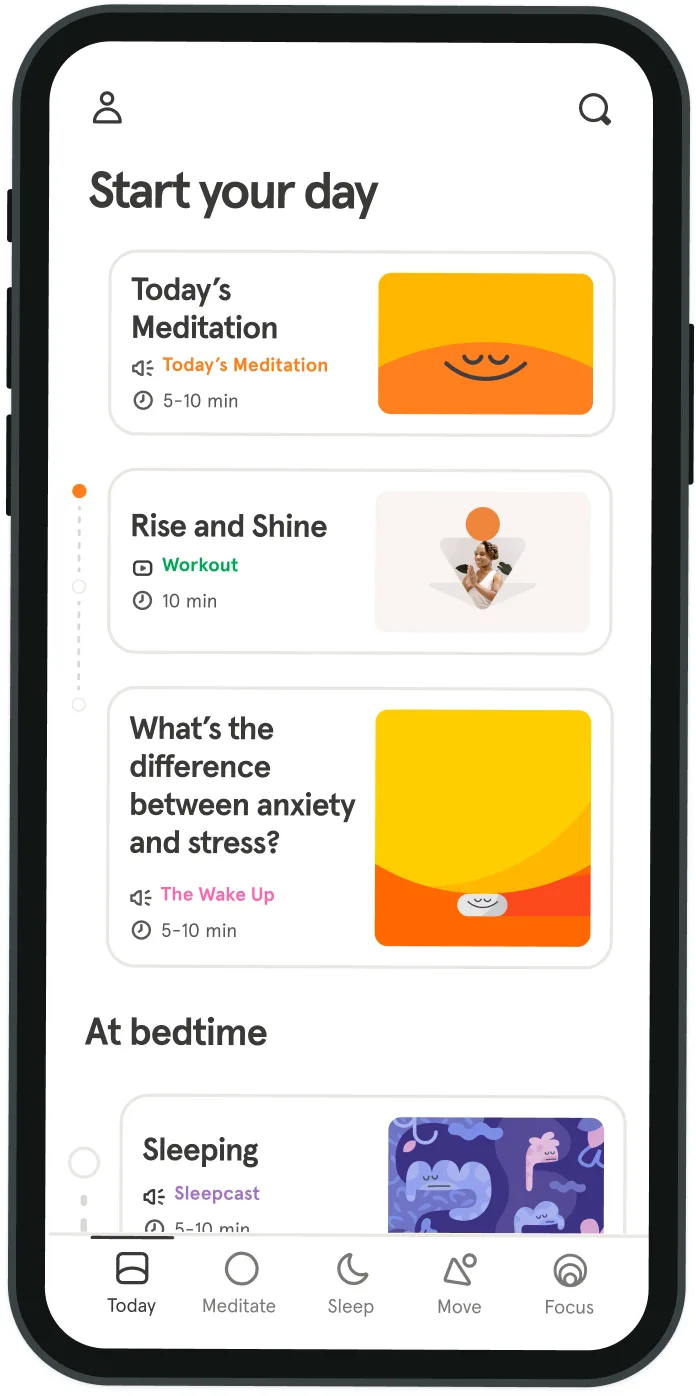

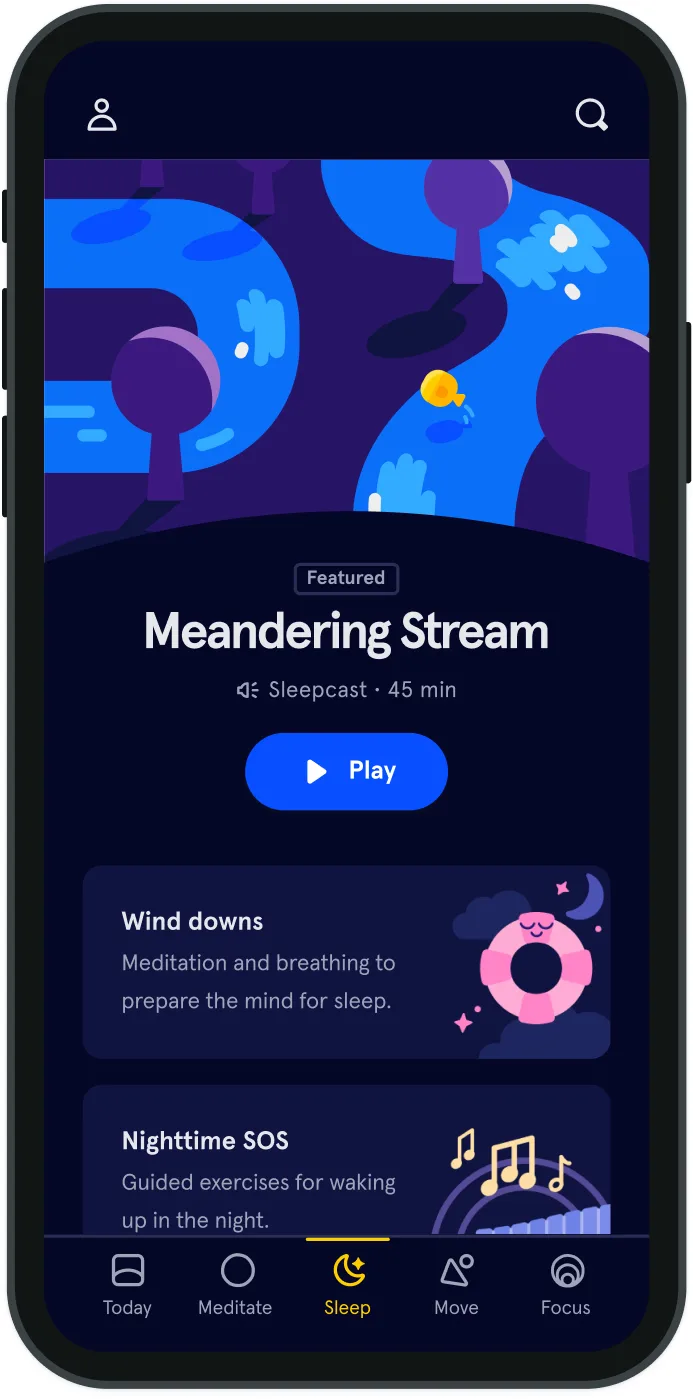

Be kind to your mind

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

- © 2024 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice