Why you can’t remember your dreams

A friend recently related her recurring dream. It’s always variations on the same theme: she’s back in high school and a classmate has taken her journal but won’t admit to stealing it. The rest of us chimed in with our own nocturnal adventures—one of us suffers from nightmares about car accidents, another had a spacey dream about running a seashell museum—but my friend Mel remained uncharacteristically quiet. “What’s up?” I nudged her. “Nothing,” she shrugged. “I just don’t really dream much.”

According to researchers, our brains boast a “consistent molecular architecture”—so why do some people seem to dream almost every night while others claim they rarely or never dream? A 2014 study reported that people who frequently remember their dreams show more activity in the temporoparietal junction of the brain, where information gets processed. This extra brain activity allows dreamers to focus on external stimuli, the study claims. It also suggested that “high dream recallers” had twice as many periods of wakefulness as “low dream recallers.” In practice, this suggested that people who remember their nighttime adventures are more responsive to sounds while sleeping, which may mean they wake up more than “low-dream recallers”. So if you’re woken up by your roommate whispering in the next bedroom, while your partner can sleep through all three alarms you set, you should count your blessings. While they catch some z’s, you're far more likely to remember your dreams. But why does this happen? According to Harvard dream researcher Deidre Barrett, as a brain wakes up “it starts to turn on processes needed for long-term storage. Thus, if we wake straight out of a dream, we have a greater chance of remembering it.”

Another factor that could determine if every last moment of that flying dream is etched into your consciousness or if it disappears entirely upon waking is how much theta brain-wave activity you have in your prefrontal cortex after waking from REM sleep. (Theta waves appear when the brain relaxes.) According to Barrett, the higher the levels of theta activity, the better your chances of recall. “Theta activity indicates a slower-paced, more relaxed brain state and greater theta activity has been linked to enhanced memory when awake.” Which might be why being “in theta” is described as a state where tasks become so automatic or memorized that the person doesn’t even need to think about what they’re doing. Theta waves aside, are there active steps you can take to increase dream recall? A 2009 study showed that meditating for 20 minutes “as well as a separate 20-minute quiet rest condition ... significantly increased theta power.” Arguably, lucid dreaming is the ultimate form of dream recall—where the sleeper is aware that they’re in a dream and can control what happens, changing the nightmare where your boss is firing the dreamer into a scenario where she offers them a promotion and a hefty pay raise to boot. A 2015 study reported that there was a "significant correlation" between mindfulness and lucid dream frequency in respondents with meditation experience. Lucid dream researcher Tadas Stumbrys, one of the psychologists who conducted the study, stressed that some skepticism should be applied, since the study was questionnaire-based (he argues a more stringent test would have delivered a mindfulness meditation program and then tested before and after) but he did mention that the questionnaire and follow-up research suggested “a lot of possible positive effects” of meditation on dreams, including “better overall dream recall, more lucid dreams and greater ability to control them, and [fewer] nightmares.”

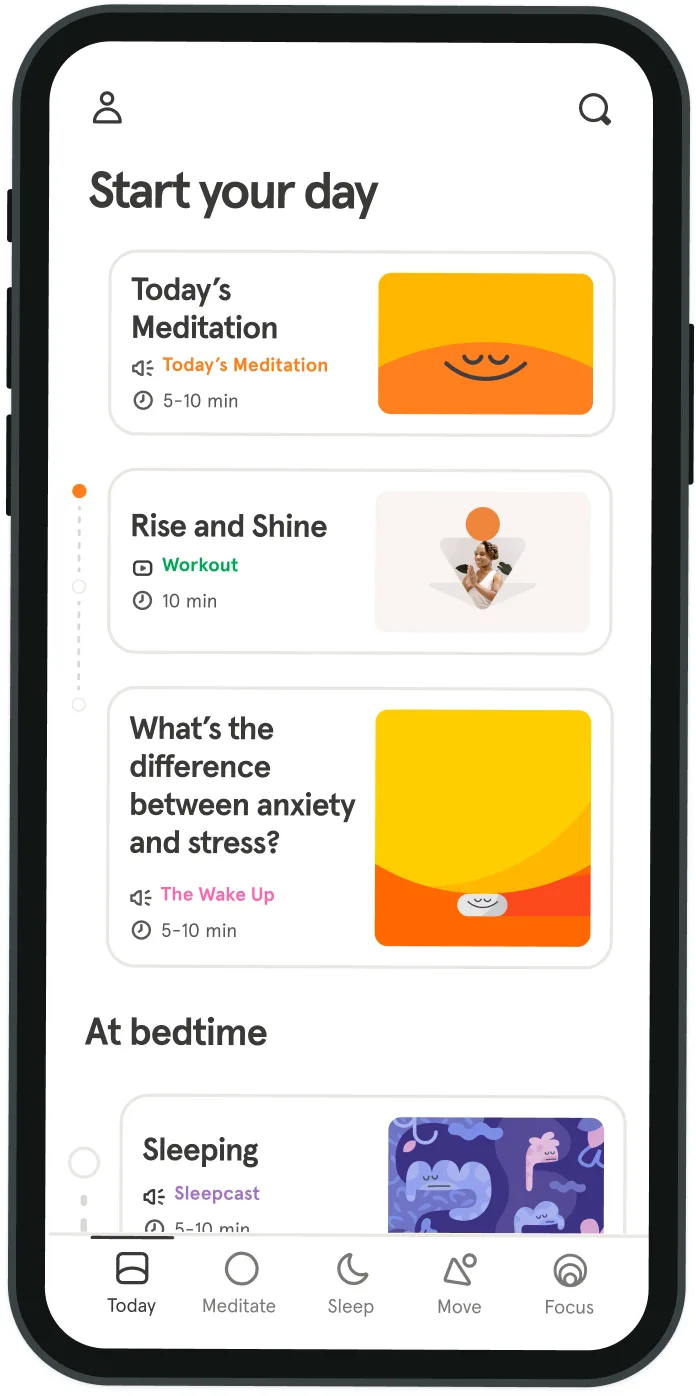

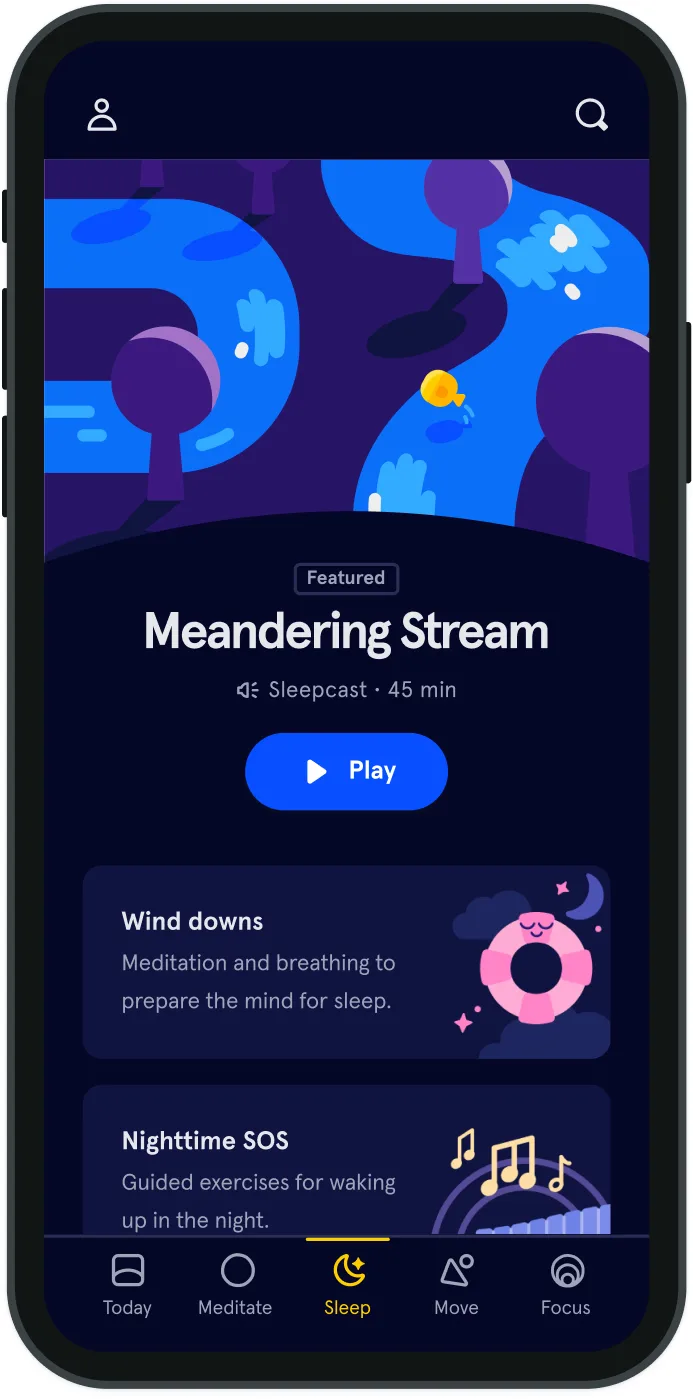

Still, if you’re worried that an absence of dream recall may indicate a less-than-rich inner life, don’t despair; it seems likely that you do dream, you just don’t remember. One study, for example, analyzed people who reported few or no dreams over the last decade. The study’s subjects exhibited “several complex, scenic, and dreamlike behaviors and speeches, which were also observed during rapid eye movement sleep” like arguing, fighting and speaking. Dr. Isabelle Arnulf, one of the neurologists who worked on the study, says it was highly unlikely that the dreamers displaying behavior like this were doing anything other than dreaming, since it was too “complex to be a sort of motor ‘automatism’” and because she’d recorded exactly the same behavior in participants who were able to remember their dreams. It’s easy to make all sorts of assumptions about dreams, simply because historically, they’ve been the province of psychologists and dream interpreters rather than scientists, meaning research is lacking in this area. However, Arnulf argues that brain imaging could slowly evolve the inclusion of dream research within the scientific community, giving researchers tangible markers to work with. And while studies so far are limited, they suggest all sorts of good things: that it could be possible to increase your chances of dream recall and that even if you don’t remember, it doesn’t necessarily mean you don’t dream at all. So while meditation may do quite a bit to enrich your waking life, turns out it could be pretty helpful for your nightlife, too. [Editor’s Note: I can attest to this. Try that Sleep pack for yourself.]

Be kind to your mind

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

- © 2024 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice