A Day With: Unspecified Dissociative Disorder

[Editor’s Note: This piece is part of an ongoing series of personal essays on what it’s like to live with a mental health diagnosis. Each piece describes a singular and unique experience. These essays are not meant to be representative of every diagnosis, but to give us a peek into one person's mind so we may be more empathetic to all.]

The first time I can remember experiencing a dissociative trance, I was 14, riding in the car with my mother down a country road at night. The world was dark all around me, and gradually I began to think that none of it was real—and neither was I.

My mom asked if I was OK. “I just feel strange,” I told her. “I don’t feel like I’m really here. I’m talking to you, but I’m not really inside my body.” She offered to take me to a doctor, but I assured her I was fine, and soon felt completely normal. The truth was, I didn’t feel like my trance was something that needed to be cured. It was a little scary, but also fascinating, like I was seeing the world and myself from a new angle. Fourteen years later, my therapist diagnosed me with Unspecified Dissociative Disorder, which means that I experience some but not all of the “clinically significant” symptoms that characterize other dissociative disorders. For instance, I don’t experience amnesia or loss of time when I go into trance-like states. Instead, I sometimes become a “depersonalized observer” of my own actions and surroundings, which was what happened during that car ride with my mother. Other people don’t usually notice when this happens unless I draw attention to it. I’m still in charge of my actions; I just feel detached, like I’m operating my body by remote control. Dissociation is an adaptive response to trauma, but it isn’t traumatic on its own. It’s a coping reflex triggered by stress, and like most coping mechanisms, has positive and negative effects. My creativity as a writer and artist is enhanced by the fact that I can lose myself in a daydream for hours at a time. On the other hand, daydreaming doesn’t help my productivity. I failed math three times in high school because it was so easy to retreat deep inside my head and be somewhere, anywhere apart from a drab classroom. And if I’m under extreme stress, I can dissociate involuntarily, stuck in a loop of anxious, depressive thinking.

With the help of therapy, anxiety medications, and a solid routine, I stay grounded more often than not, but some days are more challenging than others. One key to staying grounded on days when I’m especially prone to dissociating is to stick with a schedule. Since I work from home, I can’t rely on the structured routine of an office environment to keep me on track, so I’ve developed a flexible daily routine that allows me to get things done and still leave room for my brain to do its thing. It goes like this: 1. Shower immediately. Involuntary dissociation is mostly a problem in the hours right after I wake because I’m prone to nightmares and vivid dreams that linger long after I get out of bed. The best way to ground myself when I’m having trouble separating from a dream-like state is to head straight to the bathroom and run the shower. I listen to podcasts while I brush my teeth, shower, and go through my skincare routine. The combination of physical and mental stimuli usually brings me back down to earth. 2. Morning routine. I take a lot of comfort in doing the same things in the same order every day before work. I work in my bedroom, so it’s important to make my bed first—otherwise, I’d be tempted to just crawl back under the covers. Next, I fill my kettle for tea. While waiting for it to boil, I write down the day’s to-do list in my planner. I often remember some advice I got from a therapy group: the first item on my list is always “make a list”. That way, I get to start the day with an accomplishment already completed. 3. Marathon work session. Long, leisurely lunch hours may be a premier perk of working from home, but for me, they can be more trouble than they’re worth because I have a hard time switching between work and leisure. I prefer a solid block of work with short breaks as needed to stretch, refill my tea, and eat. 4. Take a break. On a good day, I’ll have written about 3,000 words by 6 p.m., which leaves the evening to shop, exercise, and socialize. I walk to the grocery store 3-4 times a week. The walk through my neighborhood can either be an easy, gradual way of easing back into the world after spending hours immersed in my head, or it can be a stressful, taxing foray into sensory overload—sirens blaring, cars honking, people yelling from the bus stop on the corner. If I dread the walk, I arm myself with sunglasses, a scarf, and earbuds to keep the world at bay.

When the shopping is done and I return home, it’s time to cook dinner—and, if I’m feeling up for it, chat with my housemates and see friends. On a good day, my housemates and I will dine together. If I need more alone time to recharge, I’ll make something simple and eat in my room. 5. Chill. A side-effect of being prone to slip into dissociative states is that I have to engage my mind on multiple levels in order to focus. Gone are the days when I could just stretch out on the couch and watch a movie without drifting off somewhere in the middle. If I want to watch Netflix, I’ll pick up an embroidery project to busy my hands. If I want to socialize, I’ll climb the stairs to my roommate’s part of the house and talk to her while we both play games on our phones. 6. Bedtime. I have always had trouble getting to sleep. If it’s been a good day—awoke on time, worked steadily, exercised, and ate a decent meal—then I can drift off pretty quickly. More commonly, the act of lying still in a dark room seems to be a cue for my brain to speed up. I find it helpful to listen to old episodes of my favorite podcasts, and to snuggle with my cat. The combination of soothing stimuli communicates to my brain that it’s OK to shut down for the night. I’ve discovered that another key to managing my health is to cut myself some slack without letting myself off the hook. Instead of beating myself up on the days when I don’t feel like being social and I have trouble meeting my work goals, I try to give myself the necessary time and space to process my feelings. At the same time, I know that I’ll feel better in the long run if I make the effort to keep up with my friends and stay ahead of my deadlines.When I wake up feeling like I exist at arm’s length from the rest of the world, it’s worth making an effort to stick with my grounding routine—more often than not, it works.

I’m prone to nightmares and vivid dreams that linger long after I get out of bed.

B.N. Harrison

Be kind to your mind

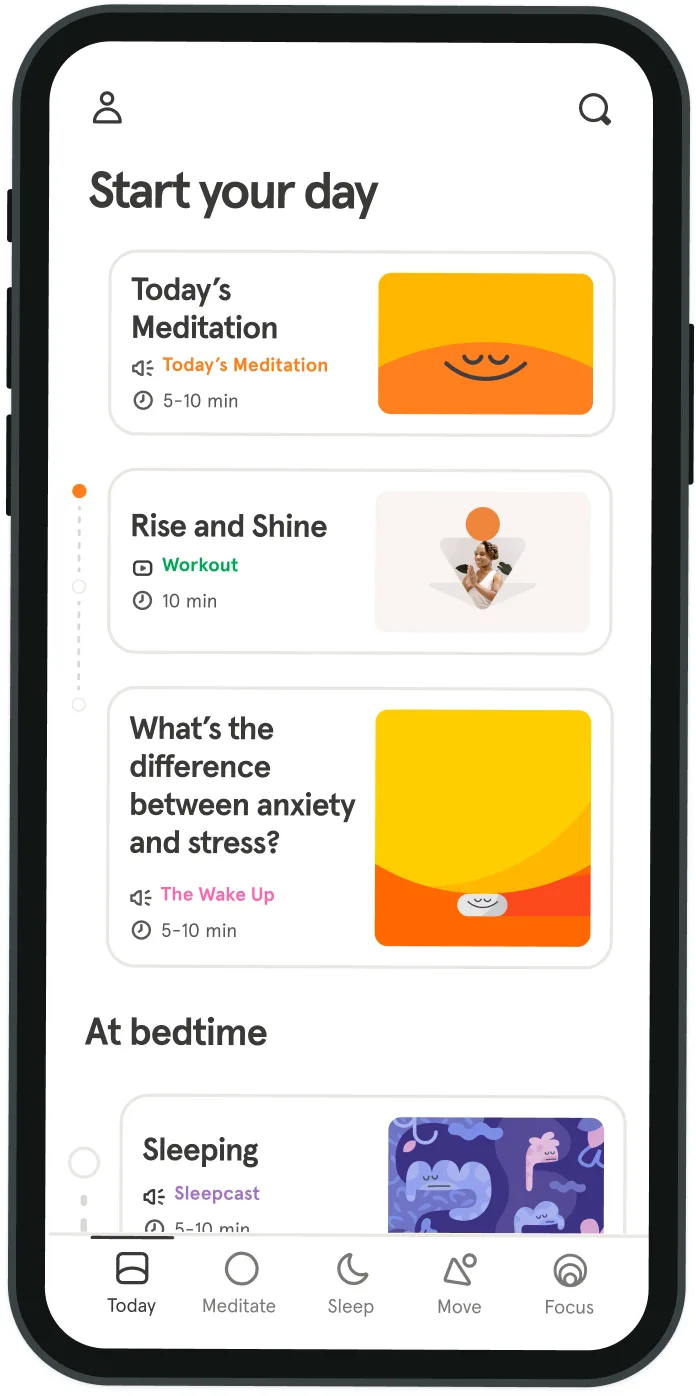

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

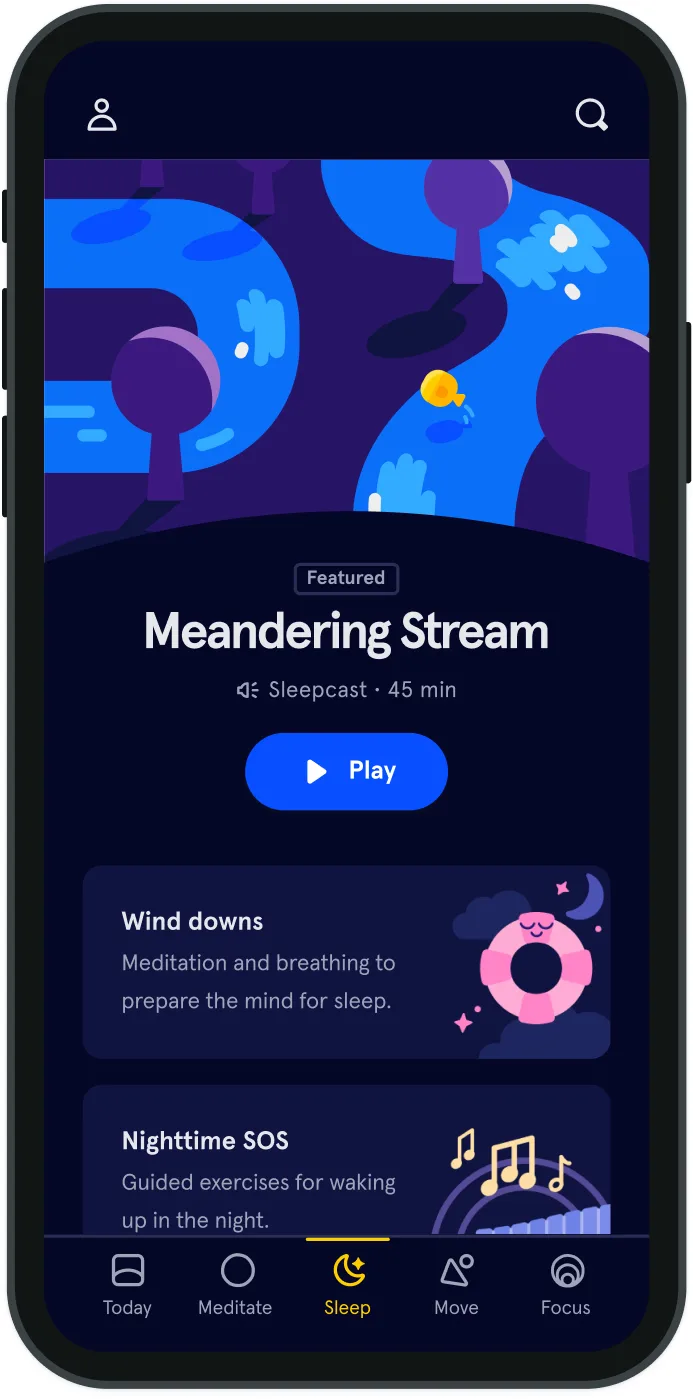

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

- © 2024 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice