A Day With: Panic Attacks

[Editor’s Note: This piece is part of an ongoing series of personal essays on what it’s like to live with a mental health diagnosis. Each piece describes a singular and unique experience. These essays are not meant to be representative of every diagnosis, but to give us a peek into one person's mind so we may be more empathetic to all.]

I was drugged and sexually assaulted when I was 21. When a police officer found me, beaten and terrified, I was incapable of telling the difference between the officer and my attacker, so I attacked him, too.

I was taken to jail and strip-searched. By the time my friends bailed me out, it was too late for a rape kit. I was charged with a felony: assault on a police officer. My punishment wasn’t the 200 hours of community service, or the formal apology to the officer, or serving on a panel where victims could tell me their stories, or being forced to take alcohol addiction classes. Those weren’t punishments—they were just distractions from the true punishment: the gripping mental anguish of going from a person to an object. For months, I suffered from dissociation. I could see my body, this animal in my apartment that I couldn’t connect with. I was haunted by flashbacks and voices, and I couldn’t tell anyone. I was afraid any treatment would find me incapacitated and derail me from completing my degree at university. A year later, a year after my classmates read about me in the police blotter, a year after the conflicted and promiscuous journey to prove I had ownership of my body, I would run away from my life, moving to the Caribbean to try to find peace. And then my temple, my fortress, my body, betrayed me: I found a lump in my neck.

I went to doctor after doctor, falling asleep with my fingers moving from the lump to my pulse and back. It took an entire year of appointments, and moving back to the states to Washington, D.C., for a doctor to finally diagnose it as a tumor, crushing the nerves in my face. It took four months for the surgery to be scheduled. I checked my pulse compulsively and drank even more. It was my perfect, quiet hell. And on a dark, winding road several months after my surgery, I begged the driver to stop—I was having a heart attack. But of course, I wasn’t. That was just the first of what would become common panic attacks. My fight-or-flight could no longer distinguish a threat. Men were a threat. Authority was a threat. Solitude was a threat. I was a threat. After two years of torment, my PTSD had blossomed into Panic Disorder, and it became crippling. The years are separated by the cities I tried to fix myself in, but my days always began the same: in the depth of night. I would wake up from horrifying dreams in cold sweats, alone. I would check my pulse, convinced my heart would beat itself to death. I would stand in the middle of train platforms, sure if I stood too close to the edge, my body would throw me over. I couldn’t hold scissors or knives, I was afraid my body would gut itself. I skipped pool parties, road trips, movies, flying, driving, tunnels, bridges, elevators, whenever and however I could. The list of triggers grew and grew, and the ways I could avoid those triggers grew, too. I left D.C. for the distraction of New York, where more than one doctor would call me dramatic and prescribe me nothing. I left the chaos of New York for the big skies of Colorado, where I would pick up a bike and learn to associate my heartbeat with athleticism, but continue to pour alcohol and long hours at work on my problems. I left the false promise of Colorado, for the sun of California. I forced myself to drive, to fly, to exist in my perceived danger. And the attacks began to fade away, until someone very dear to me, someone I’d kept my struggle from, and who had kept their own struggle from me, had a psychotic breakdown, developing schizoaffective disorder. Only then did I begin the real work of changing my lifestyle, finding a therapist, and beginning a meditation practice.

I went to doctor after doctor, falling asleep with my fingers moving from the lump to my pulse and back. It took an entire year of appointments, and moving back to the states to Washington, D.C., for a doctor to finally diagnose it as a tumor, crushing the nerves in my face. It took four months for the surgery to be scheduled. I checked my pulse compulsively and drank even more. It was my perfect, quiet hell. And on a dark, winding road several months after my surgery, I begged the driver to stop—I was having a heart attack. But of course, I wasn’t. That was just the first of what would become common panic attacks. My fight-or-flight could no longer distinguish a threat. Men were a threat. Authority was a threat. Solitude was a threat. I was a threat. After two years of torment, my PTSD had blossomed into Panic Disorder, and it became crippling. The years are separated by the cities I tried to fix myself in, but my days always began the same: in the depth of night. I would wake up from horrifying dreams in cold sweats, alone. I would check my pulse, convinced my heart would beat itself to death. I would stand in the middle of train platforms, sure if I stood too close to the edge, my body would throw me over. I couldn’t hold scissors or knives, I was afraid my body would gut itself. I skipped pool parties, road trips, movies, flying, driving, tunnels, bridges, elevators, whenever and however I could. The list of triggers grew and grew, and the ways I could avoid those triggers grew, too. I left D.C. for the distraction of New York, where more than one doctor would call me dramatic and prescribe me nothing. I left the chaos of New York for the big skies of Colorado, where I would pick up a bike and learn to associate my heartbeat with athleticism, but continue to pour alcohol and long hours at work on my problems. I left the false promise of Colorado, for the sun of California. I forced myself to drive, to fly, to exist in my perceived danger. And the attacks began to fade away, until someone very dear to me, someone I’d kept my struggle from, and who had kept their own struggle from me, had a psychotic breakdown, developing schizoaffective disorder. Only then did I begin the real work of changing my lifestyle, finding a therapist, and beginning a meditation practice.

If, in that unusually warm January in 2007, after a strange man held me to the ground, someone, anyone, had encouraged me to see a therapist, if my school had made one available, if my insurance had covered it, if I’d had the tools to talk about my mental health, if there had been a single obvious resource for that discussion, maybe I wouldn’t have spent years unable to leave the house without borrowed clonazepam in my pocket. Maybe I wouldn’t have lived in fear of people, of opportunity, of myself. Maybe I wouldn’t have had to save myself. Maybe I could have saved someone else. Now, as the Managing Editor of Headspace, I work for a company that not only believes in taking care of our minds but champions it. That is why, with great pleasure, I am kicking off the “A Day With Mental Health” series with our Chief Science Officer, Dr. Megan Jones Bell. Every experience with a mental health diagnosis is different, but in this series, we’ll feature just a handful of the millions of stories. Our hope in sharing these stories is to create empathy, to create a world where discussing our mental health isn’t taboo, and to remind us all, we’re not crazy—we’re just human. If you are suffering, you are not alone. In this series, we’re going to shine a light on the minds of regular people trying to get by, to go to work, to pay bills, to love, and to live, just like us. Mental health affects us all. It’s time we look inside.

The "A Day With Mental Health" series is brought to you by Headspace and Bring Change to Mind (BC2M). BC2M is a nonprofit organization built to start the conversation about mental health, and to raise awareness, understanding, and empathy. They develop influential public service announcements (PSAs) and pilot evidence-based, peer-to-peer programs at the undergraduate and high school levels, engaging students to eradicate stigma. Because science is essential to achieving this mission, BC2M’s work is grounded in the latest research, evaluated for effectiveness, and shared with confidence. Headspace is proud to partner with them as we shine a light on the day-to-day experiences of living with a mental health diagnosis. This series will publish weekly on Headspace’s the Orange Dot. Read the rest of the series here.

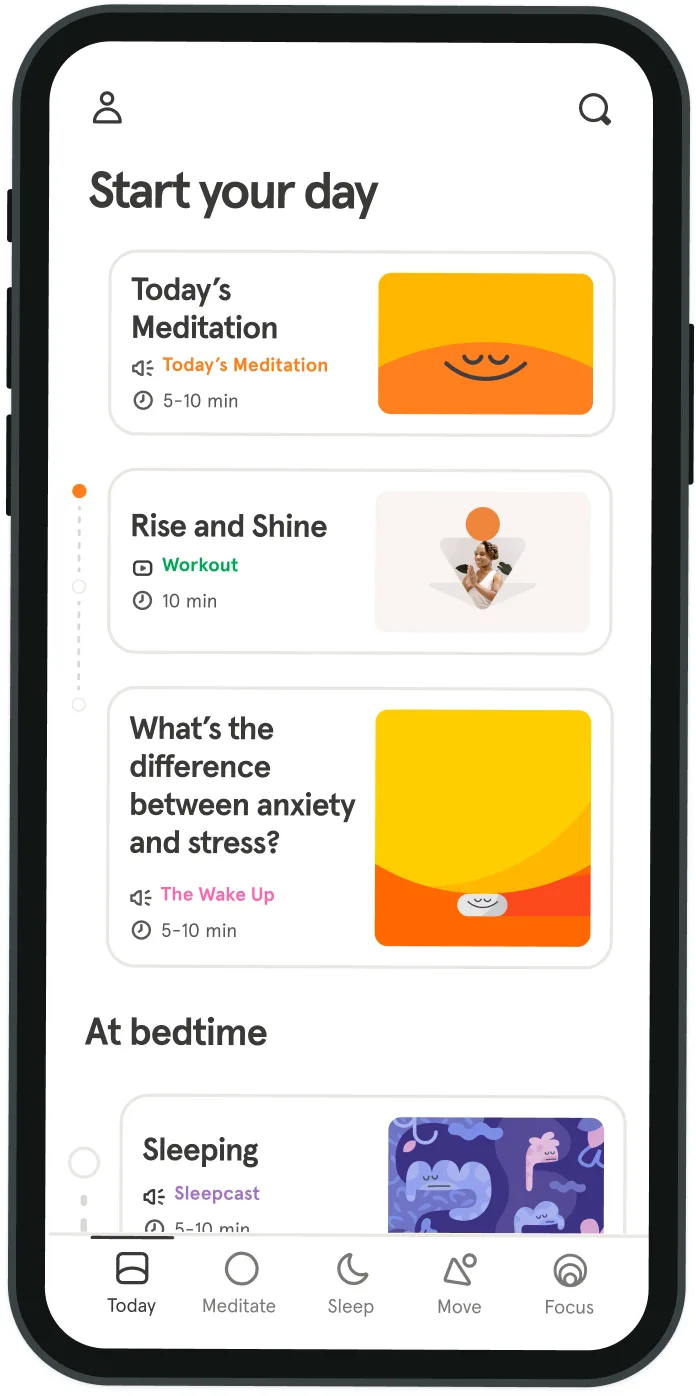

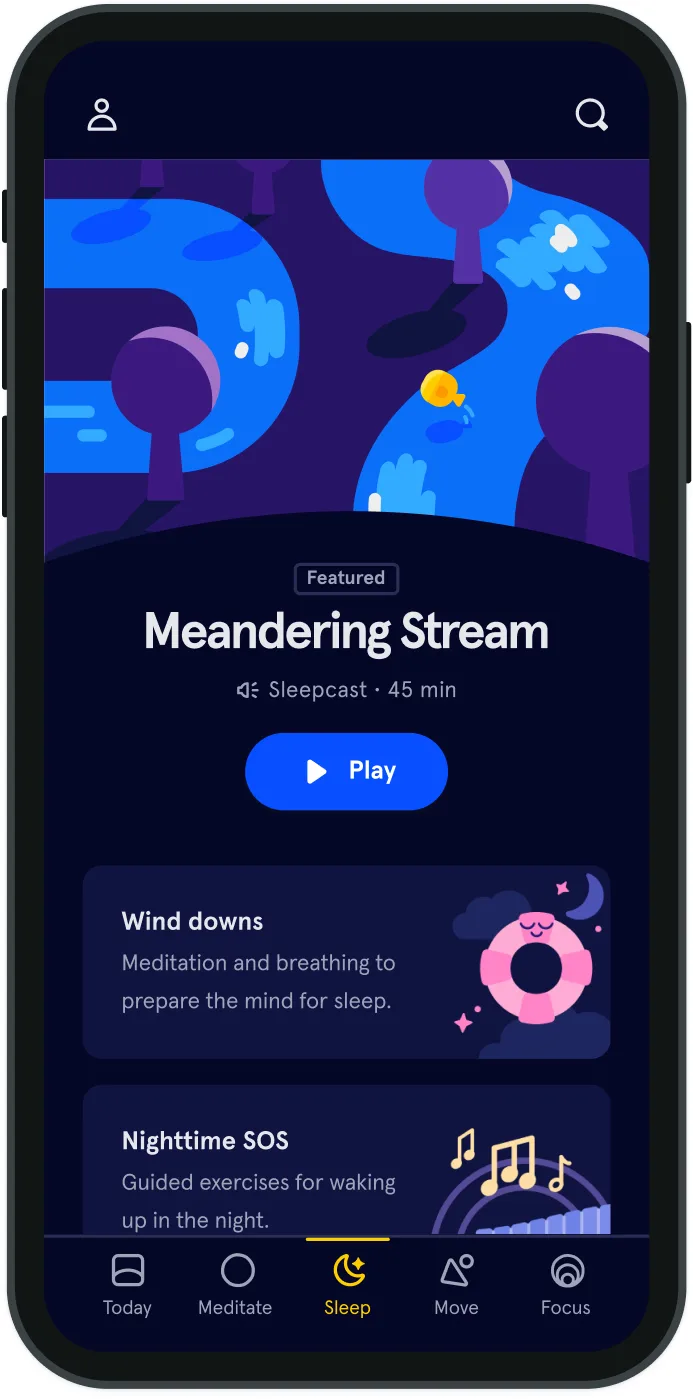

Be kind to your mind

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

- © 2024 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice