Can you grieve someone while they’re still here?

I always knew my dad would be a fantastic grandpa. He wasn’t always the best father since his untreated mental illness often meant that things like paying the bills were forgotten in favor of exploits like driving to New York to promote his Next Big Idea.

These weren’t qualities fit for a father who needed to provide stability to his children, but I secretly loved them anyway. I would watch my father scoop up my little cousins and toss them into the air as they shrieked with laughter, knowing that my children would one day enjoy a grandpa unlike any other. This turned out to be true, but not in the way I imagined. When I was in college my father’s bipolar disorder changed tracks. Instead of leaning toward mania, he was consumed by depression. He moved in with his mother, spending each day sleeping on a window seat in her living room, curled like a cat as the light filtered in. If he was having a good day he would half-heartedly raise his arm to greet me when I walked in. On bad days, he didn’t move. When I climbed onto the window seat and told him I was pregnant, he smiled but didn’t rise. Sometimes we lose a family member before they die. The father I grew up with is, in a very real sense, gone. His loud personality, love for walking, and passion for creativity haven’t been seen in a decade. Instead, he is slow and subdued, bogged down by a brain that has been damaged by depression and stroke. He’s easily confused and often tired. I am grateful that my father is alive when so many people do not survive depression, but the grief brought on by his illness is undeniable. I grieve for myself, my siblings, my father, and my daughter, who will never really know the man who raised me. I’ve had to disregard my vision for the future and begin rewriting one for this new father. It’s a situation that families dealing with mental illness, addiction, dementia and other conditions know well. Family members become almost unrecognizable, but we still interact with them every day. The pain of this paradox is made worse because many people dealing with them don’t realize that they are grieving, says psychotherapist Melanie Smithson.

“There’s confusion because we tend to associate grief with a death or breakup, not with someone who has changed dramatically,” Smithson says. This also leads to a lack of support from our communities. “People don’t get it,” she says. “If your dad died, people would be supporting you—but I bet you didn’t have that experience.” She’s right. Outside of support groups for family members of those with mental illness, few people acknowledge my sense of loss. Many people in this situation are afraid to grieve for the family member they once knew because they think that means giving up hope for cure or recovery. “We don’t understand that we can have multiple emotions simultaneously,” Smithson explains. Glimpses of our lost love one can make these feelings even more raw. Maybe he’ll get better, I sometimes think, even after ten years. I wrote you a story, he’ll tell my daughter, and I will be transported to the many weekends I spent with dad at fairs and book signings promoting his children’s books. When I see the few scribbled lines that constitute his stories now, the tears come because it’s gut-wrenching to know that the passion we shared is still alive somewhere deep inside but inaccessible to him.

Just as we can make space for multiple emotions, we can embrace two aspects of our loved one: grieving for who they once were and accepting who they are now. Some family members may be afraid to connect with their loved one as they are now and risk yet another loss. However, as with any relationship, that vulnerability is part of the process, Smithson says. “You have to be open to the possibility of being heartbroken and know you can handle it.” She uses the example of getting a new pet after a beloved animal has died. The new pet provides companionship but does not negate the grief over the companion we have lost. It can be the same in dealing with loved ones who are vastly changed or can no longer occupy the same role in our lives. “We have to let go of any expectations of who they should be or what we should get from being with them,” Smithson says. “By letting go of expectations, we let ourselves be present to what’s here now.” For me, the very thing that caused so much of my grief has become a balm for it: my daughter’s relationship with my father. Because she never knew my dad before his depression, she doesn’t know what she is missing. Although this makes me sad, it gives my daughter an amazing ability to meet my dad where he is. She loves visiting his group home and doesn’t mind that sometimes he is unkempt or withdrawn. She loves her Papa no matter what. Watching her has taught me to find joy in my father as he is now. On occasion, however, I scoop my daughter up and toss her high into the air, and as she shrieks with laughter I tell her stories about how Papa used to be.

Be kind to your mind

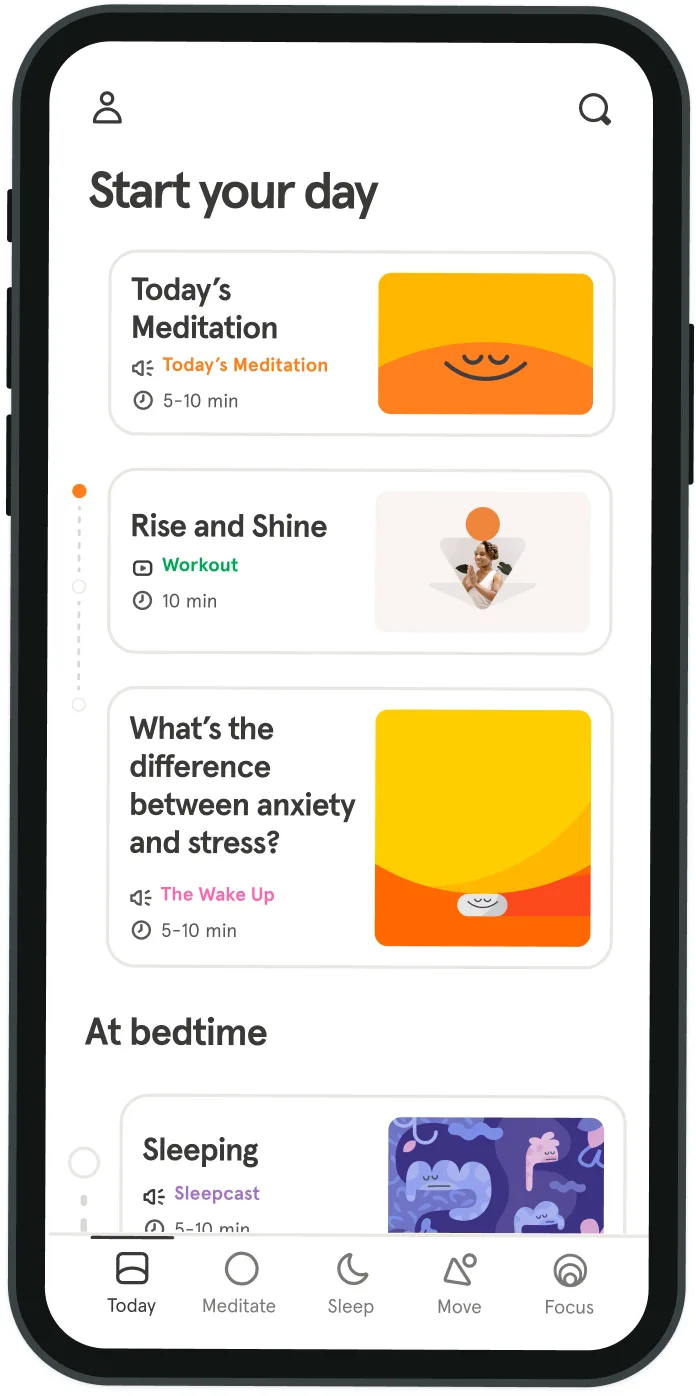

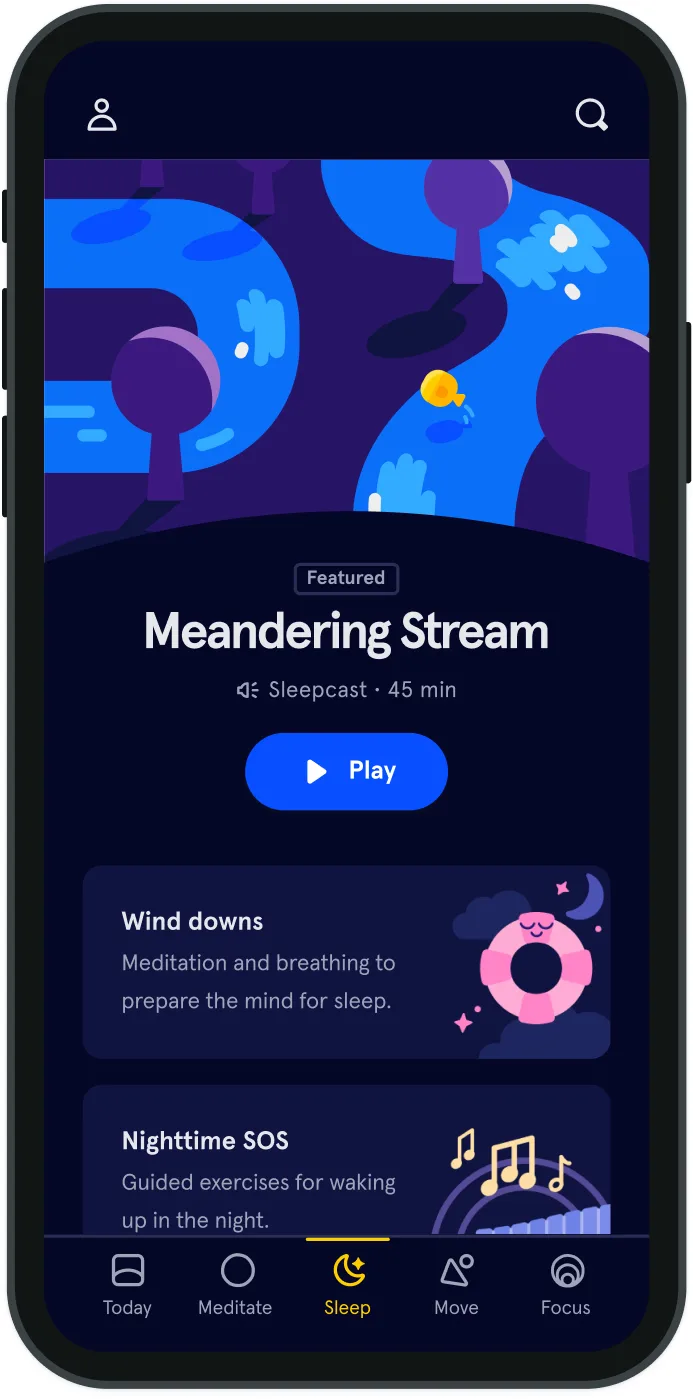

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

- © 2024 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice