Philosophical proof that kindness is the best policy

You have a decision to make that involves another person. A friend, maybe. But half of your decision becomes trying to anticipate what your friend will decide. Should you admit to that time you lied to them about being too swamped at work to travel the thousand miles to their destination wedding? Do you keep up with the lie and risk being too guilty to ever look at them normally again, or even worse, risk that they’ll be too upset to ever look at you normally again? How will they react to your honesty? Will they ever discover the lie? You measure the pros and cons. You imagine all the potential outcomes.

When you have a choice that involves another person, acting rationally to better your own situation is natural. Or so goes the crux of the prisoner’s dilemma, a typical example of a game analyzed in game theory that suggests why two rational people might choose to not “cooperate” with one another, even if they’d likely benefit from doing so. The game is usually presented using a scenario wherein two people are arrested for a crime they committed together. They’re each given the opportunity to say the other person is guilty, or they can choose to remain silent. They can’t communicate with one another. The potential outcomes are:

- A and B betray the other, they each serve 2 years

- A betrays B and B remains silent, A serves 0 years and B serves 3 years

- A and B both remain silent, they each serve 1 year

The idea here being that even though option three would lead to both parties serving the least amount of time, people tend to risk option two, in hopes of bettering their personal situation by serving zero time.

In a study on how human friendship favors cooperation (what we call option 3), researchers looked at the iterated prisoner’s dilemma and suggested that friendship may influence an individual’s likelihood to cooperate. “Previous knowledge of the other player’s attitude toward cooperation may positively affect an individual’s decision to cooperate during the game,” they state. Yet, even when individuals are familiar, we can’t always anticipate how they’re going to act. A simple example we likely all can relate to is the often torturous crush. In this scenario, let’s say you and a good friend secretly have a crush on each other, but neither knows how one feels about the other. Do you say something? Do you keep quiet? Do you risk making things weird for your entire friend group? There are many scenarios that can play out here, so you consider each possible outcome, rationally. In scenario one, you admit your feelings to your crush, they admit they feel the same, and everyone lives together in perfect crush harmony. You’ve cooperated. In scenario two, you admit your feelings, but your crush is caught off guard or doesn’t feel ready to admit their feelings back. You’re both left feeling bad and awkward, and your friendship is essentially ruined.

In scenario three, you don’t confess. Instead, you spend the rest of your years living the slow agony of pretending a friendship is just a friendship. But, you do remain friends. Just friends. Without knowing what the other “player’s” attitude toward cooperation is, it’s hard to make a decision. Yet, it should be simple. Choosing to cooperate will lead to a better situation in spite of what the other player decides. In the study, the researchers found that humans cooperated more when playing with a friend versus a stranger. “The sense of trust in the other player's willingness to reciprocate the altruistic act is probably an important prerequisite favoring cooperation and it may explain the differences between friends and unfamiliar players,” they conclude. It makes sense; someone you have a relationship with is more likely to factor your well-being into their decision making process. But, if you choose to think as a group even when the other players involved might be strangers, you’re all likely to leave with a better sense of well-being. Although it’s rational to think about your own well-being and consider a situation in which you benefit personally, thinking rationally isn’t always the best scenario. It’s important to be mindful about the people around us, not just because it benefits them, but because it benefits our perception of ourselves and the situation. In the end, knowing someone is benefiting from your choice can be an added bonus of positivity.

It’s important to be mindful about the people around us, not just because it benefits them, but because it benefits our perception of ourselves

Alexa Schlomo

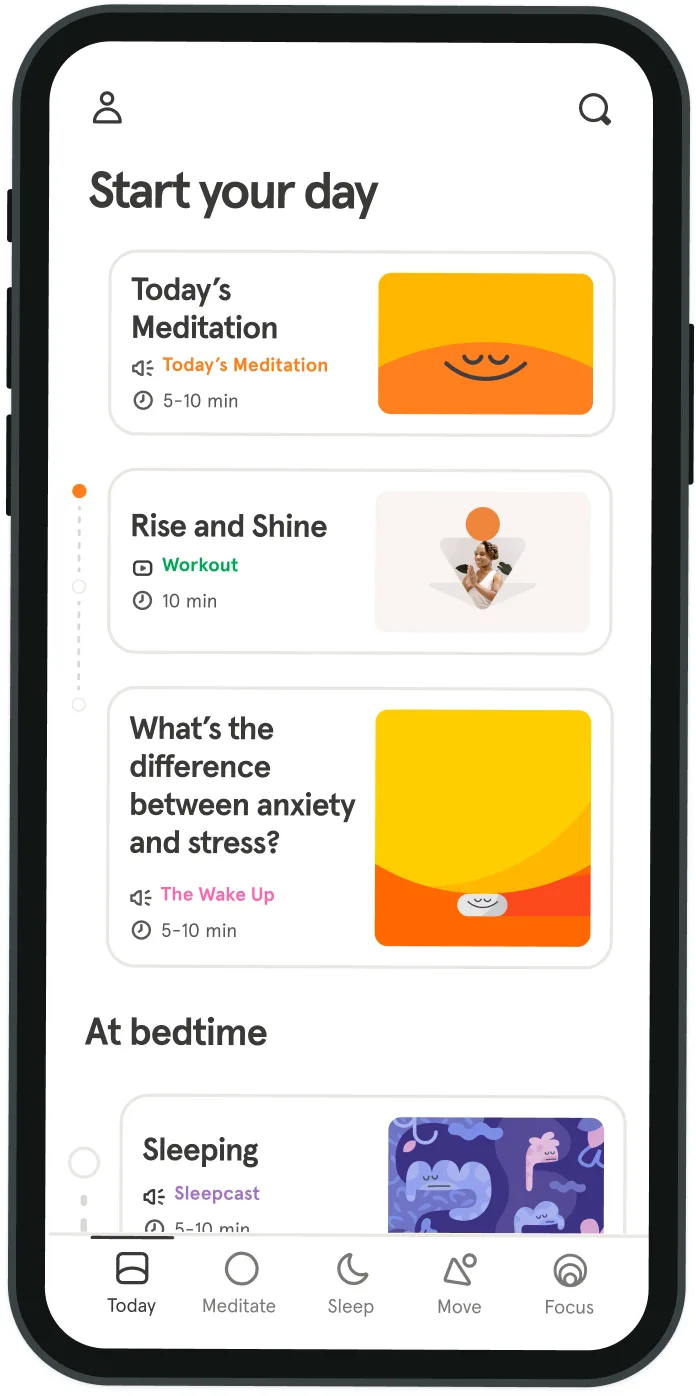

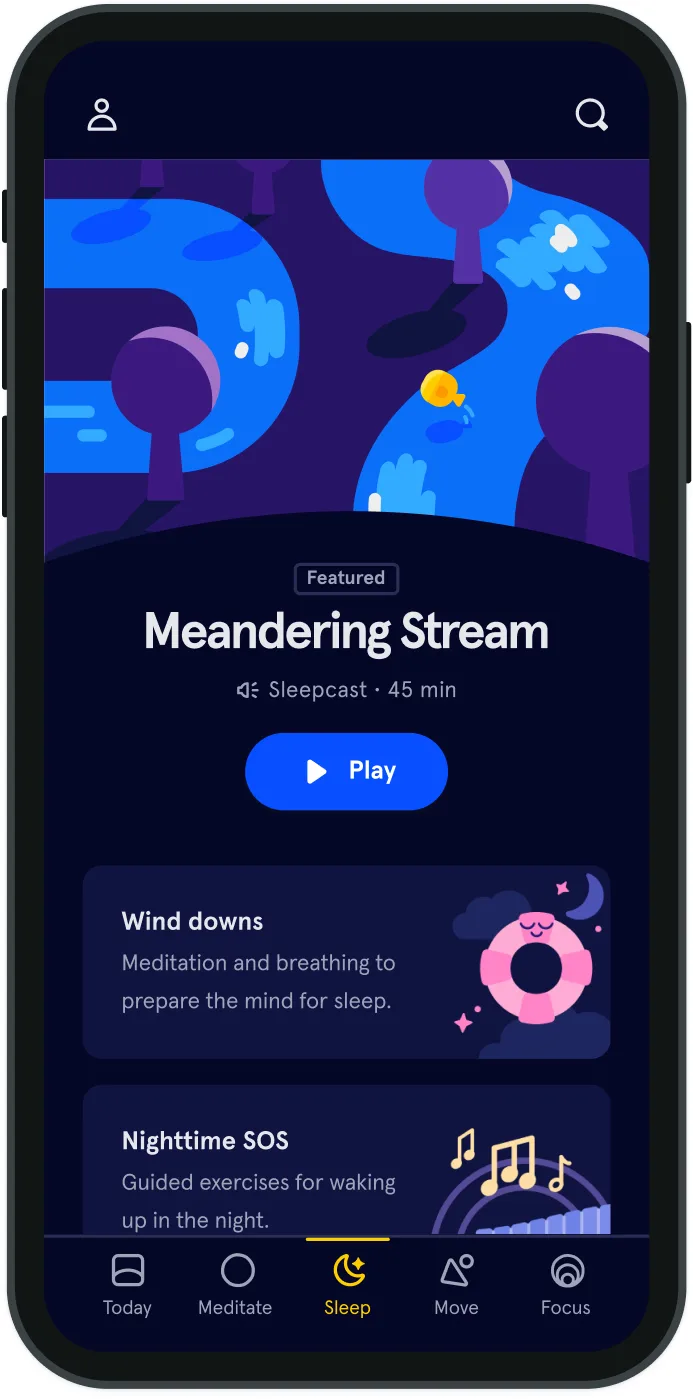

Be kind to your mind

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

- © 2024 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice