Trust me, I’m a stranger

Advice. We’ve all needed it, benefitted from it and ignored it. And, particularly if we trust the person giving it, it can be hugely beneficial. So why exactly is it that we’re sometimes more willing to turn to strangers, rather than our friends, for words of wisdom?

A fine art

The notion of divulging our secrets to someone we barely know is not new. Over the ages people have visited priests, mystics and even psychics for help when navigating life’s choppy waters. Today, we’re more likely to share our dilemmas in advice columns and radio talk shows, or even to pay to speak to a therapist who is professionally required to know us much better than we’ll ever know them. I spoke to LBC Radio’s “agony aunt”, Lucy Beresford. She compares our urge to share our problems over the airwaves to confessing to a priest, “An important dimension is anonymity. I think it’s something we’re all desperate for.” Much like the screen in a church confessional, separating priest and penitent, the distance of a phone call or email exchange preserves the anonymity of the advice-seeker. “It’s a one-way communication - I’m not going to then tell them what’s going on with me, and ask what they think.” In other words, we can unburden ourselves fully, without being expected to listen in kind. But what about that silent audience of listeners or readers that witness your request for help? Mary Fenwick, agony aunt at Psychologies magazine says, “There is a sense of bringing your issue to the campfire, or a virtual tribe of like-minded people”, she says, which elicits comfort, and a willingness to share. Agony aunts or other advice-givers may well be strangers (they don’t know us, after all), but crucially, they don’t feel like the strangers they are. The perceived intimacy that comes from hearing someone dispense wisdom on a regular basis encourages us to share as if with a friend. And it’s the spot between safe distance, and closeness, that we seem to be most comfortable in. It is, as Fenwick says, “a step up from asking a stranger, but less exposing than having to talk to someone face-to-face.”

So, just how did this all begin?

The first ‘problem pages’ appeared around 1690 in The Athenian Mercury. Edited by one John Dunton, he launched the publication after finding he had no one to ask about his adulterous urges without revealing his identity. Readers wrote in with ponderings from the existential, “Is the soul born with the body?”, to the troubling, “Dancing, is it lawful?” (in case you were wondering – yes). Psychologist and coach Maurits Kalff suggests that there are a few reasons that asking anonymously has been with us so long. “When sharing problems about how we relate to everyday life, we show vulnerability. In asking someone you don’t know, there may be less shame…. Shame often gets in the way of sharing, because we’ve all been taught to put up a brave face.” “A stranger doesn’t have an agenda for you. We’re surrounded by loved ones, who know us at our best, but as soon as love is in the picture, these people are stakeholders… so their advice may not always be unbiased,” Kalff says. Isn’t this a little selfish of them? “There’s nothing malicious about it, because often it’s an unconscious process. Your loved ones aren’t aware that they’re advising something that may actually suit them too.” So for the most objective, sage advice on what’s closest to us, we may do well to look further afield.

You weren’t the only one wondering…

Turns out there are benefits for readers as well as advice seekers. It’s comforting to know you are, in fact, not the only one wondering whether to stick with a cheating spouse, if you should move to a new city, or how to take the plunge with that long overdue career change. We relieve the sense of isolation that a particular problem may cause us. A problem shared, is a problem halved, as the saying goes. Perhaps the act of asking for advice has value in and of itself. In seeking counsel, we also create distance between what we’re grappling with, and how we feel about it. As Fenwick puts it, “the act of writing helps us to order our thoughts,” giving new perspective to an old problem. Seeing a problem in print, or heard aloud, as well as having it acknowledged, may be just what’s needed – we may realize we’ve been worrying over nothing, or immediately see where we’ve gone wrong. And of course, without the same emotional attachment, the advisor may be best poised in guiding us, taking us out of our heads, and (hopefully) into a space of clarity. As advice-givers write for everyone they tend to find a broad audience. It’s understood that agony aunts will give advice that’s general advice, that won’t get bogged down in details. Maybe a certain amount of simplification can be a good thing. Beresford agrees, “when people come to me, we often get to the heart of the matter quickly.” In these generalities, devoid of detail and context, we see ourselves reflected. We’re reminded of the sheer universality of human experience (as any agony aunt would attest, there are only so many types of problems). And like a home remedy, or your grandmother’s secret recipes, we trust in what survives, what’s been tried and tested, in the stories of people who’ve come back from the place we’re going.

Take my word for it

So, are we more likely to follow advice from a radio show or news column, even if it’s general or meant for someone else? Perhaps, we look to others to voice what deep down, we intuitively know already, but struggle to enact. Cultivating honesty with ourselves happens gradually, with each breath, and is not likely to snap into place with some stern words from a motherly figure. Regardless, good advice can provide a much-needed new perspective. But no matter the communal wisdom at our disposal, we may need to find our own way. As the poet, Edna St. Vincent Millay, said, “I am glad I paid little attention to good advice; had I abided by it, I’d have been saved from my most valuable mistakes.”

Shame often gets in the way of sharing, because we’ve all been taught to put up a brave face.”

Sadia Ahmad

Be kind to your mind

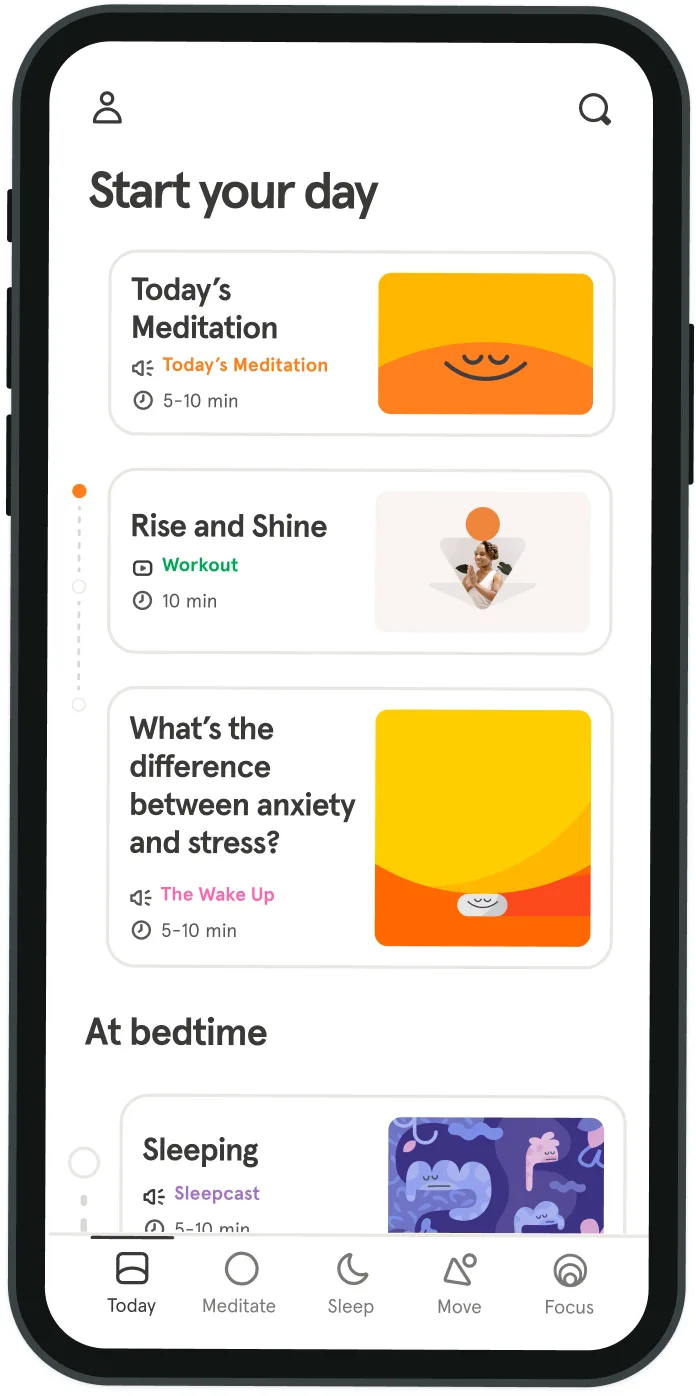

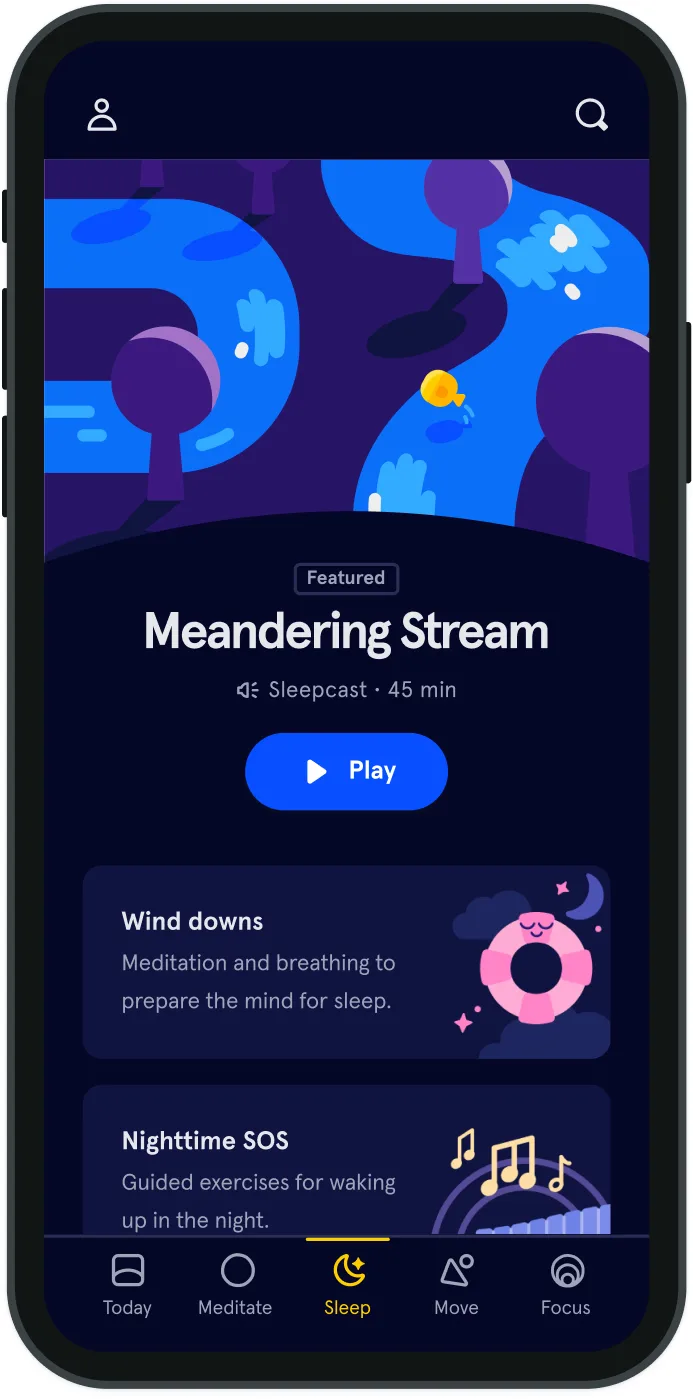

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

- © 2024 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice